This 7 minute video gives a great overview of the 33,000 Everyday Artists project. It includes interviews with various participants and wonderful visuals of people engaging with the project.

Thanks to Nick Hand for making the film.

This 7 minute video gives a great overview of the 33,000 Everyday Artists project. It includes interviews with various participants and wonderful visuals of people engaging with the project.

Thanks to Nick Hand for making the film.

Although a traditional survey seems at odds with the playful and creative intentions of the project, we’ve realised it’s a helpful and efficient means of gathering data from 33,000 Everyday Artists participants.

It’s been challenging writing the survey questions because we want to gather useful and meaningful data but also be short and sweet so as to not put off respondents and in keeping with the ethos of the project.

Whenever writing survey questions, it’s important to firstly decide exactly what it is you’re trying to find out. As such, the objectives for this survey were:

We used the platform Survey Monkey and the final questions were:

We also offered the incentive of a £50 Amazon voucher to entice people to respond.

For any readers who have taken part in 33,000 Everyday Artists, please fill in the survey here. The deadline for completing the survey is Friday 8th April.

ArtsProfessional, the UK’s leading arts magazine, have featured a case study article on 33,000 Everyday Artists. ‘A small town of everyday artists‘, written by Laura Speers and Jo Hunter offers a snapshot overview of the project and some initial observations.

ArtsProfessional, the UK’s leading arts magazine, have featured a case study article on 33,000 Everyday Artists. ‘A small town of everyday artists‘, written by Laura Speers and Jo Hunter offers a snapshot overview of the project and some initial observations.

Read the full article here.

‘Institutional Critique’, an approach that emerged in the 1960s from the art world, is a form of commentary that critically reflects on the concept and social function of art and the institutions it is housed in.

Institutional critique seeks to critique the ideological, social, economic and representative functions of a museum or gallery. It also aims to make visible the historically and socially constructed boundaries between the inside and outside, elitism and populism, and the public and private. The outputs produced by institutional critique can take multiple forms including interventions, critical writings and (art)political activism.

The approach, which was originally an artistic practice conducted mainly by artists, is now being used in numerous and differing contexts.

Institutional critique does not aim to oppose or abolish the institution, but rather improve, modify and progress it.

Institutional response to institutional critique

According to Shiekh (2006), during the 1990s it became fashionable for curators and art directors to commission and hold the critical discussions at their own art gallery or museum. This resulted in the institutional critique framework, the artist’s role and the critique being taken over by the very institution it stood against and ultimately being institutionalized.

Shiekh (2006) has argued: “the total co-option of institutional critique by the institutions (and by implication and extension, the co-option of resistance by power)” made the critical method obsolete.

Although this institutionalization presents a dilemma, it is possible that institutions integrating the critique do not necessarily render the method redundant. For example, institutional critique can critique this very practice. Furthermore, it’s important that institutions listen to, and act on, the issues raised by the analytical approach so integrating it may not always be a bad thing.

Historically it was a subject from outside the institution who conducted the critique but now it is being performed by administrators, curators and directors. However, having an ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ position in relation to an institution is increasingly difficult.

One of the leading author on institutional critique Andrea Fraser (2005) has argued in her essay From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique, movement between an inside and outside of the institution is no longer possible. This is because the structures of the institution have become totally internalized. Fraser (2005: 283) writes:

We are the institution. It’s a question of what kind of institution we are, what kind of values we institutionalize, what forms of practice we reward, and what kinds of rewards we aspire to.

Fraser suggests we are to create critical institutions (“an institution of critique”), which can be established through self-questioning and reflection as this is institutional critique in practice.

Institutional critique and 33,000 Everyday Artists

The approach can be potentially illuminating in relation to this research project as we aim to understand King’s as an institution, its values and culture. Indeed, 33, 000 Everyday Artists can be seen to be a form of critical artistic practice itself.

Porter et al. (2000) have argued for institutional critique as an activist methodology for changing institutions. They suggest it can be employed as an activity of rhetoric and composition aimed at change. This change involves improving the conditions of those affected by and served by institutions. The authors highlight the possibility of rewriting our own disciplinary and institutional frames.

Sosnoski (1994: 212) notes, “Institutions, like all social contracts, can be rewritten. However this is not a simple process.” A university is a critical institution but needs to be critical of itself. Institutional critique offers an analytical tool to do this.Through interrogating the culture of King’s, evaluating the institution’s conditions and all of our everyday complicities, we can change the culture of King’s and make it a better place to study, work and be part of.

Following Fraser (2005), as the institution is internalized, embodied and performed by individuals, engaging in institutional critique, demands we ask questions ultimately about ourselves.

References

Andrea Fraser (2005). From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique. Artforum, September 2005, XLIV, No. 1, pp. 278–283.

James E. Porter, Patricia Sullivan, Stuart Blythe, Jeffrey T. Grabill and Libby Miles. (2000). Institutional Critique: A Rhetorical Methodology for Change. College Composition and Communication, Vol. 51, No. 4: pp. 610-642.

Simon Shiekh. (2006). Notes on Institutional Critique. Transform: European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies.

James Sosnoski. (1994). Token Professionals and Master Critics: A Critique of Orthodoxy in Literary Studies. Albany: SUNY P.

We’ve slightly modified our first research question so it is now as follows:

The change means we are now focusing on ‘structures’ and ‘institutions’ (which draws from the meta-theory of critical realism, specifically Fleetwood’s 2008a article Institutions and social structures) replacing the original wording of ‘distinctive features’.

The slight alteration is designed to make the research focus on ‘process’ rather than ‘outcome’. This means the research findings will be more useful because it will look to understand the process of building an everyday culture of creativity and the shifting priorities required to allow for playful and imaginative behaviors. Exploring conditions, structures and institutions will mean moving beyond evaluating the specific achievements (or otherwise) of the 33kEA project.

As researchers, we now need to identify the principle structures and institutions to look at. These might include, but are not limited to: norms; beliefs; routines; processes; protocols; and regulations.

Methodological issues

The project is ambitious and fraught with methodological difficulty (e.g. additionality; limited time and resources; reification of single ‘culture’ at King’s; ‘light touch’ evidencing). We need to think carefully about how much (or little) we can reasonably infer from this experiment – couched as it is in the language of ‘hypotheses’. 33kEA will not be able implement all its aims in such a short period (one imagines); highlighting what has not been possible (Popperian falsification) will be as valuable as what has been made possible.

There is a danger of reifying ‘culture at King’s’, giving the false impression that there is a single unified and homogeneous culture. In fact, most of the university does not see or interact in any way with the rest (albeit pockets of interdisciplinary activity exist). This being the case, one suspects that the ‘answers’ from this project are very much context-specific (what ‘works’ for medicine might be quite different to that for Arts & Humanities, for example).

The issue of ‘light touch’ evidencing is problematic. The nature of the project is to actively introduce (promote/sustain) a (counter)culture of everyday creativity in King’s. If we wade in with rigorous and overt research we will potentially kill the very thing being created. We need to collect appropriate data without it interfering with the experiment. So – ideally, in every case where we are collecting data we need to make this intrinsic to the process in such a way that it is collected organically and without being imposed top-down.

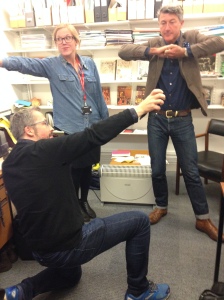

With a research project like 33,000 Everyday Artists, which has a number of team-members, stakeholders and participants, there are invariably a lot of meetings. Rather than capture these important conversations and often inspiring discussions in the usual meeting minutes format, or in the form of research notes, we’ve decided we’d like to capture them in a creative way so in keeping with the ethos of the everyday artist experiment.

Some ideas for different methods of capturing meetings in creative way that I’ve come up with so far include:

So far we’ve done the post-it note and freeze-frame method which were both enlightening. These methods really do convey something about a meeting that would not have been articulated otherwise, and often get at the heart of what was discussed. The creative methods can also demonstrate how differently each person feels a meeting went and so is a useful way of noting attendees’ varying responses. The fact that it’s fun is important too as it ends a meeting on an active and enjoyable note, rather than with people shuffling or dashing out of the room as they normally do.

This photograph shows the results of the ‘freeze-frame’ method we used yesterday at the end of one of our meetings. We all came up with very different physical responses then explained them which was extremely illuminating.

This photograph shows the results of the ‘freeze-frame’ method we used yesterday at the end of one of our meetings. We all came up with very different physical responses then explained them which was extremely illuminating.

Nick was impersonating David and his sling from the famous biblical story of ‘David and Goliath’ i.e. facing ‘the beast’ and overcoming the odds to be successful. The stance also captured the discussion we had about disrupting the rules and challenging the status quo when conducting research which was a key point that came out of the meeting.

It’s tough coming up with research questions when you start out on a project because it’s a fundamental component that impacts the entire research process so is important to get right. The reason the research question is crucial is because it determines the focus of the study, and also guides all stages of the inquiry, analysis and documenting.

It’s tough coming up with research questions when you start out on a project because it’s a fundamental component that impacts the entire research process so is important to get right. The reason the research question is crucial is because it determines the focus of the study, and also guides all stages of the inquiry, analysis and documenting.

The research question(s) need to identify the areas of concern, be clear and feasible and also be worth investigating so contributes knowledge and value to the field.

Based on these factors and extensive discussion with the 33kEA team, Dr Nick Wilson, the PI of the project, came up with the below:

33k Everyday Artists background factors for consideration:

Suggested research questions:

Notes:

RQ1: This question challenges us to think carefully about what it is we are seeking to ‘embed’ at King’s. What are the ‘distinctive features’ that allow us recognise (and celebrate) such a culture? Are these features (in)visible? Are some of its features visible (because they are legitimised), whereas others are not (overlooked, excluded)? Is it, in fact, impossible to list a particular set of features as comprising such a culture (hence the ‘if any’), because it depends from context to context? Or, are a key set of ‘distinctive features’ necessary? How might we understand these features (e.g. a mix of internal; external; personal; organisational; PEST?)?

RQ2: This second question focuses on process; to what extent are the ambitions of 33KEA actually realisable? What are we learning through this ‘experiment’? How might the process be different in different parts of the university (which parts should we categorise?)? To what extent is there an everyday culture of creativity already (and if so, how is this manifested in terms of RQ1)? How might a proactive campaign help (or hinder) the development of such a culture, where it already exists?

The two research questions will be challenging to research because they interdependent. However, we cannot answer one without the other so will form a mutually-informing framework for our research.

Although the research questions might be slightly refined as we progress, it is useful to have delineated what exactly the project is about at the this stage and where we will be focusing our attention.

53 Million Artists is an action research project and social movement that is both about and emerging out of everyday life. 53 Million Artists seeks to address constraining attitudes, practices and behaviours of the monotonous everyday to incite people to be more engaged and imaginative through harnessing creative agency.

53 Million Artists is an action research project and social movement that is both about and emerging out of everyday life. 53 Million Artists seeks to address constraining attitudes, practices and behaviours of the monotonous everyday to incite people to be more engaged and imaginative through harnessing creative agency.

By suggesting a range of ‘creative challenges’ (from photography to going on a walk), participants are encouraged to upload a post describing their experience, with a photo or video if they wish to, onto the 53 Million Artists website. This straightforward process has been captured in the following instructions: “Make time. Do Stuff. Think about it. Share it.” By making an intervention, we are critiquing institutional discrimination on a societal level, and the everyday habits on an individual level that reinforce the status quo, though promoting creative practice as force of for the potential transformation of everyday life.

53 Million Artists was created by two former arts organisations leaders who were frustrated with the direction in which the ‘the arts’ was going. One of them took time out from her everyday job and dedicated time to ‘creative challenges’ set by family, friends and co-workers. It was during this time of ‘defamiliarisation’ (Lefebvre, 1991a) that she was re-enchanted with art and recognised herself as an artist who had lost her creative disposition and tendencies. Perceiving art as a universal human capacity, rather than belonging to the gifted few she worked with in her everyday job, she sought to establish a movement that would inspire the whole population of England (53 million) to identify as artists and experience the personal transformation of everyday life that had so profoundly affected her.

Creating a platform and campaign to communicate this message has brought on board a team of helpers, as well as researchers to record and analyse the development and success of this movement. As the name suggests, the focus is on being an artist, rather than the artwork. As such, the slogan “just do it” is significant in simply encouraging people to challenge themselves and do something different from their everyday life, without focusing on the result and whether it is ‘good’ or ‘beautiful’ or not.

The project asks the simple question, what would life be like if we spent more of our time and energies living as artists – seeing, hearing, and feeling the world more deeply? The French philosopher Henri Lefebvre argued against the separation of art from life and the general fragmentation of human activities in favour of a revolutionary aesthetics of humanist Marxism. He interpreted Marx as expounding a particular artful or aesthetic disposition:

He imagines a society in which everyone would rediscover the spontaneity of natural life and its initial creative drive, and perceive the world through the eyes of an artist, enjoy the sensuous through the eyes of a painter, the ears of a musician and the language of a poet. Once superseded, art would be reabsorbed into an everyday which had been metamorphosed by its fusion with what had hitherto been kept external to it.

It is through this re-absorption or ‘re-habituation’ of art into everyday life, through initiatives such as 53 Million Artists, that dis-alienation can be achieved and lead to human flourishing and thus a transformation of everyday life.

53Million Artists is a practical, applied, theoretical, lived, everyday initiative and communication with a growing public. At a grassroots level, 53 Million Artists has made an intervention at two work organizations based in London, and run workshops, during the four-month pilot phase. The next stage of the project will be expanded to reach a greater diversity of people in terms of age and background as well as geographically, by going into schools, prisons, residential homes, hospitals, businesses and so on. At a national level, it is hoped the project will continue to stimulate conversations and debates about what ‘art’ is and what it means to be an artist.

In the pilot phase, resisting and reclaiming terms such as ‘art’, ‘artist’, and ‘creative’ has been somewhat achieved by calling attention to the privileging of this discourse by pre-existing, occluded or invisible structures and institutions, in what we have identified as ‘artism’.

The 53 Million Artists researchers are currently writing a journal article that maps out how we might ‘re-habituate’ (i.e. make a regular habit of) art in everyday life. Using the data collected thus far, we are suggesting 53 Million Artists makes an intervention in this area through encouraging a reflexively-oriented everyday practice that has the potential to transform people’s lives.

The 53 Million Artists researchers are currently writing a journal article that maps out how we might ‘re-habituate’ (i.e. make a regular habit of) art in everyday life. Using the data collected thus far, we are suggesting 53 Million Artists makes an intervention in this area through encouraging a reflexively-oriented everyday practice that has the potential to transform people’s lives.

We are using the framework of ‘habituation’ by Steve Fleetwood (2008) to explain how this social change will occur. According to Fleetwood, habituation involves the following three main processes:

53 Million Artists seeks to re-habituate art and everyday life by substituting one set of values and beliefs (limiting and constraining views of what art is and who can be an artist) with another (open, mindful and permission-giving beliefs).

Fleetwood argues that institutions (as opposed to social structures) can directly affect agents’ intentions and actions; they can cause ‘reconstitute downward causation’. This means they create and mould new habits. Hodgson (2002: 170) further explains what is meant here:

What have to be examined are the social and psychological mechanisms leading to such changes of preference, disposition, or mentality. What does happen, is the framing, shifting and constraining capacities of social institutions give rise to new perceptions and dispositions within individuals. Upon new habits of thought and behaviour, new preferences and intentions emerge.

As such, 53 Million Artists aims to give rise to new perceptions and dispositions in individuals regarding art and creativity, which will be achieved by doing (“just do it” interventions in workshops; creative challenges; sharing online etc) as well as generating important discussions on a local and national level about art and artists in this country. It is hoped this will then result in different preferences and intentions, and ultimately a habit of doing art in everyday life.

In thinking about 53 Million Artists, we might usefully draw on expressive arts therapy (Knill et al. 2005) – a form of therapy that specifically adopts art as a central medium of its practice – to explore a ‘rite of restoration’ and what it could mean in this everyday context. The general goal of interventions in rites of restoration is the increase in the range of play. What is being ‘restored’ here is the space to play with art, or as an artist; this is a form of restoration that restores “broken or separated cultural bindings, reconnecting with a sense of cultural identity, and most importantly, the possibility of becoming.” (Wilson 2014: 219).

In thinking about 53 Million Artists, we might usefully draw on expressive arts therapy (Knill et al. 2005) – a form of therapy that specifically adopts art as a central medium of its practice – to explore a ‘rite of restoration’ and what it could mean in this everyday context. The general goal of interventions in rites of restoration is the increase in the range of play. What is being ‘restored’ here is the space to play with art, or as an artist; this is a form of restoration that restores “broken or separated cultural bindings, reconnecting with a sense of cultural identity, and most importantly, the possibility of becoming.” (Wilson 2014: 219).

Three aspects of this rite of restoration have been identified (Knill 2005: 83). The first is a process of decentering; the point of this is to “move away from the narrow logic of thinking and acting that marks the helplessness around the ‘dead end’ situation in question” (Knill 2005: 83). As Levine notes, “in order for therapeutic change to occur, there must be a process of destructuring in which one’s old identity comes into question and is taken apart” (Levine 2005: 45). The second is the provision of an expanded play space; here, it is important to note that play is “imagining what is not present” (Kimmel 2000: 198). Kimmel observes that play “is the subjective capacity of the human being to disengage from the pervasive presence of an existential and operational modality – the otherwise inseparable unity of time and space – which makes possible a representation and projection of an ‘objective world’” (Kimmel 2000: 198). Third is the process of holding the play space open.

In terms of 53 Million Artists, the first aspect is framed around the mission of the social movement and the doing of creative challenges, regardless of background, creed or ability. The expanded play space is provided through 53 Million Artists’ web presence and its developing public conversation about art and artists. This provides what might be thought of as a ‘ritual container’ (Knill 2005: 83). The focus in the research of this project is more in terms of the third aspect – holding the play space open. For this to happen requires the engagement of a range of “ordained or graduated” individuals or “change agents” (Knill 2005:77).